- Kishore Mahbubani on BRI as a strategic counter to containment: China’s Belt and Road Initiative is reshaping Eurasian and maritime Asia through infrastructure-led connectivity and redefining regional geopolitics.

- ASEAN’s neutrality amid rising US–China rivalry: As great-power competition intensifies, ASEAN must maintain unity, but the Philippines’ 2026 chairmanship may test the grouping’s cohesion.

- Asia’s multipolar future with China, India, and new institutions: India’s rapid rise and Asia’s expanding institutional ecosystem—RCEP, AIIB, BRICS+—signal an emerging multipolar order.

By Sebastian Lim

A “NEW ASIA” is emerging—more self-assured, more interconnected, and increasingly central to global geopolitics. Former ambassador Kishore Mahbubani, one of Asia’s most influential strategic thinkers, believes the region is entering a decisive chapter shaped by shifting economic weight, US–China rivalry, and the reconfiguration of global institutions.

In a recent conversation with New Asia Currents, he shared his reflections on China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), ASEAN’s neutrality, India’s rise, and the expanding institutional landscape that smaller states must learn to navigate.

BRI and the new Eurasian–Maritime geography

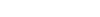

China’s Belt and Road Initiative remains one of the most consequential drivers of Asia’s transformation. Mahbubani sees it as a long-term strategic response by China to prevent any successful containment policy by the United States.

“BRI is very carefully thought out,” he says. “It is designed to help many countries by improving their infrastructure. In doing so, these countries build good relationships with China and are therefore less likely to join any US-led containment strategy.”

He notes that Western criticism of BRI—especially the narrative of “debt trap diplomacy”—has been disproven, citing scholars such as Deborah Brautigam who have repeatedly demonstrated that such claims lack evidence. Instead, BRI has delivered tangible connectivity benefits across continents. Indonesia’s Jakarta–Bandung high-speed rail is a flagship example, while even developed economies like Greece have seen port revitalisation through Chinese investment.

Geopolitically, Mahbubani argues that BRI reshapes Eurasia by reviving land connectivity from Central Asia to Europe, creating new trade corridors that dilute maritime chokepoints historically controlled by Western naval powers. In maritime Asia, BRI accelerates regional interdependence, deepening China’s ties with ASEAN through ports, rail lines, and industrial parks that feed regional value chains.

“BRI will prove to be an asset for participating countries,” he concludes, “especially in the long run.”

ASEAN neutrality in a polarised environment

ASEAN’s successful summit in Kuala Lumpur this year reaffirmed the grouping’s tradition of neutrality and strategic balance. But the region’s delicate equilibrium will be tested in 2026 when the Philippines—one of America’s closest regional allies—assumes chairmanship.

Mahbubani acknowledges that the US–China contest is accelerating, driven by “the iron laws of geopolitics” as a rising power approaches the global No. 1. He expected this trajectory and wrote about it years earlier. A temporary ceasefire in 2025 moderated tensions, mainly because China demonstrated its ability to retaliate with export restrictions on rare earths and critical minerals, pressing the US toward a negotiated pause.

“But once the ceasefire is over,” he warns, “the contest will resume.”

This rivalry will reverberate through Southeast Asia, which sits at the geographic epicentre of Sino-American competition. ASEAN states will feel pressure from both sides.

“We need to ask whether BRICS is a sunrise or a sunset organisation. I believe it is a sunrise organisation. And if many of our neighbours are joining, Singapore should take a fresh look at BRICS too.” - Kishore Mahbubani

“That is why the 11 ASEAN countries must stick together,” he stresses. “They must remain friends with both China and the US—especially where trade is concerned.”

How the Philippines balances its alignment with the US with ASEAN consensus will be a key test of the grouping’s cohesion. For Mahbubani, ASEAN’s strength has always been its ability to maintain its neutrality and equidistance to avoid being drawn into great-power rivalry.

India’s civilisational rise and the Asian balance

India’s ascent is another structural force shaping Asia’s future. Mahbubani highlights India’s extraordinary economic transformation: “In 2000, the UK economy was 3.5 or 3.6 times larger than India’s. Today, India’s economy is bigger. By 2050, it will be four times the size of the UK.”

This shift, he believes, should prompt the British to give up their permanent seat on the UN Security Council in favour of India, whose global role will inevitably expand.

India’s civilisational identity—rooted in its long-range view of history and strategic culture—makes it unlikely to become a formal Western ally. Nor will it be subsumed into a China-centric Asia. Instead, Mahbubani foresees India charting its own independent path, a “third way” that reflects both its rising confidence and its desire for strategic autonomy.

He hopes that India will eventually reconsider its decision not to join the Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP), the world’s largest free trade agreement. “It would be good for India if it joins,” he says, noting the long-term benefits of deeper economic integration with Asia.

Asia to sustain multipolarity with new institutions and new choices

With both China and India ascending simultaneously, the question arises: can Asia maintain stable multipolarity? Mahbubani believes it can—provided the institutional architecture continues to evolve.

RCEP, AIIB, and BRICS+ are prime examples of this emerging architecture.

RCEP, signed in 2020, has weathered the post-pandemic downturn and now provides a robust framework for trade and investment across the Asia-Pacific. AIIB, launched by China in 2015, fills a critical gap left by the World Bank’s retreat from infrastructure financing.

“For many developing countries,” Mahbubani notes, “infrastructure is a priority—ports, airports, highways, railways. And AIIB provides the vital financing.”

BRICS+ is expanding rapidly, attracting new members like Saudi Arabia, UAE, Egypt, and Ethiopia. The organisation is gaining momentum in Asia. Indonesia has joined; Malaysia has applied; Thailand and Vietnam are exploring membership.

“We need to ask whether BRICS is a sunrise or a sunset organisation,” he says. “I believe it is a sunrise organisation. And if many of our neighbours are joining, Singapore should take a fresh look at BRICS too.”

For smaller countries like Singapore and Malaysia, the message is clear: the regional order is no longer defined solely by Western-led institutions. Navigating the new landscape will require agility, openness, and a willingness to engage emerging platforms that reflect Asia’s growing voice.

The dawn of a confident Asia

Mahbubani’s central thesis is optimistic: Asia’s future will be shaped not by conflict but by connectivity, not by division but by the rise of multiple poles of economic and political gravity. The task for Asian states—big and small—is to keep engaging the world, stay anchored in cooperation, and ensure that the region’s rise remains peaceful.

“As Asia grows,” he says, “its progress will benefit the world. The challenge is to manage this transition wisely.”