Leading proponent of the Sundaland hypothesis, Dr Danny Hilman Natawidjaja shares why this submerged Ice Age continent could reshape our understanding of prehistory.

- Sundaland’s vast Ice Age landmass and biodiversity made it a likely birthplace of early societies

- New evidence from Gunung Padang may predate Mesopotamia and Egypt

- Submerged ruins, flood myths, and linguistic clues hint at a sophisticated lost culture — possibly Atlantis

By Sebastian Lim

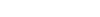

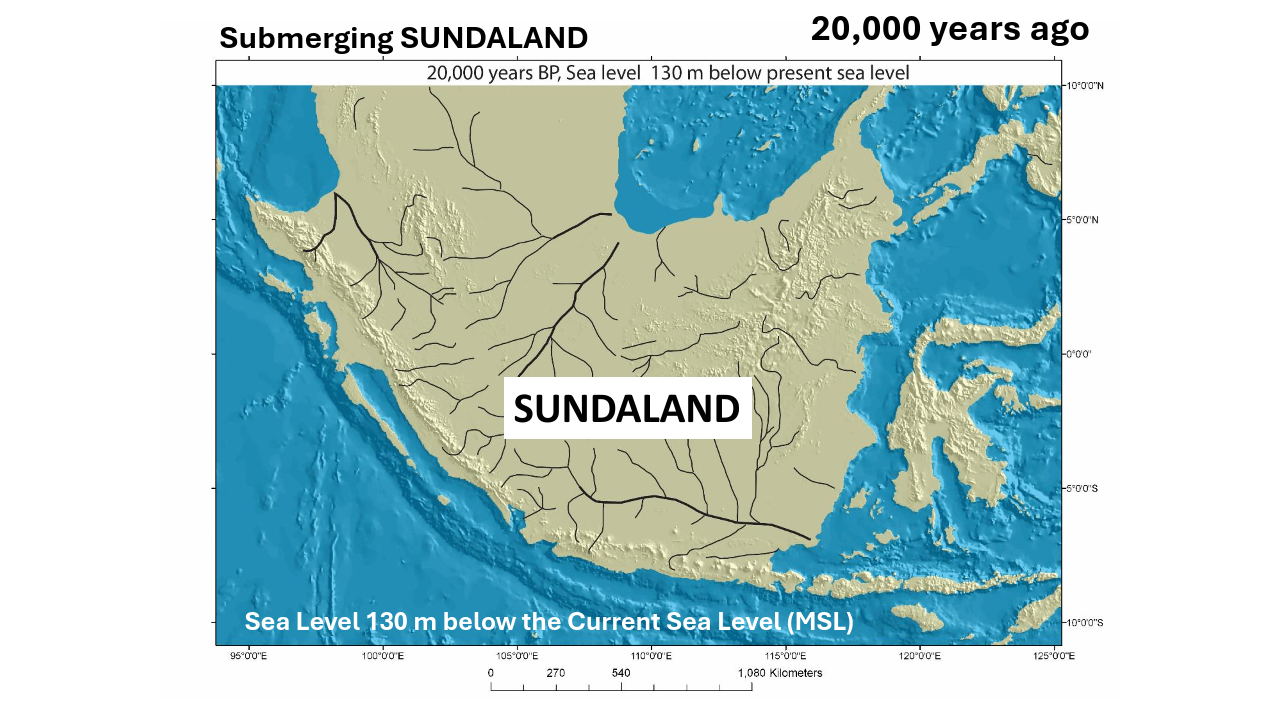

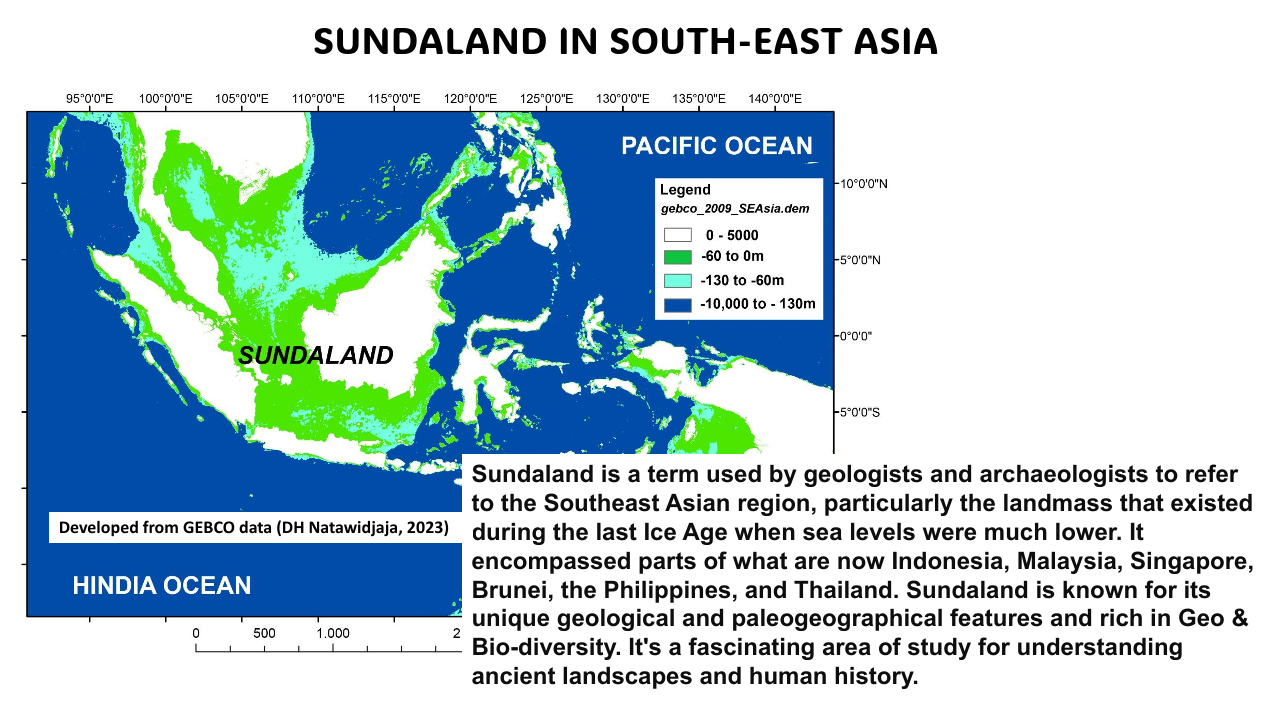

LONG BEFORE the towering pyramids of Egypt or the ziggurats of Mesopotamia, an ancient civilisation may have flourished in a region now hidden beneath the seas of Southeast Asia. The Sundaland hypothesis proposes that a vast submerged landmass — connecting today’s Malay Peninsula with Sumatra, Java, and Borneo — could have been home to early, complex societies over 10,000 years ago.

One of the most prominent voices championing this theory is Prof Dr Danny Hilman Natawidjaja, an Indonesian geologist whose research at the enigmatic megalithic site of Gunung Padang in West Java is drawing renewed international interest. He believes that Sundaland may not only have nurtured ancient human settlements — but could also be the real-world location of Plato’s Atlantis.

Ice Age Eden

“Sundaland was quite literally a paradise during the last Ice Age,” says Dr Danny. With sea levels about 120 metres lower than today, what is now a chain of Southeast Asian islands was once a single, expansive subcontinent — larger than modern India. Rich in forests, freshwater rivers, and a temperate climate, it would have offered ideal conditions for agriculture, trade, and civilisation-building.

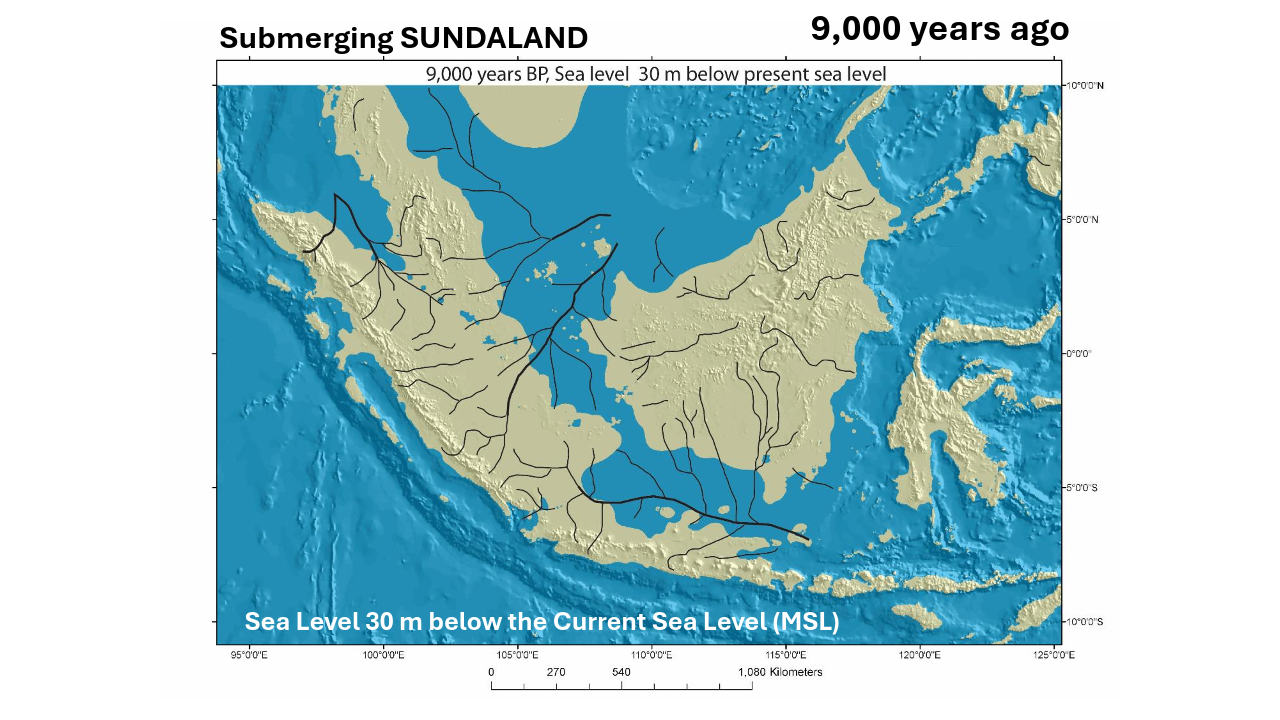

But this vast world was gradually lost as the Ice Age gave way to the Holocene epoch. Rising seas — driven by melting glaciers — inundated coastal settlements in two key phases: an abrupt, possibly seismic-triggered flood, followed by slower, sustained submersion. Dr Danny argues that these events could be the historical foundation for flood myths worldwide — including the story of Noah’s Ark and Plato’s Atlantis.

Gunung Padang: The smoking gun?

Located in the lush hills of West Java, Gunung Padang at first appears to be a simple hilltop dotted with ancient stone pillars. But subsurface imaging and core drilling reveal something astonishing beneath: a multi-layered man-made structure possibly spanning more than 16,000 years of construction.

The deepest layer, Unit 3, may date back to over 16,000 years ago, based on radiocarbon testing. Unit 2, lying above it, is around 8,000 years old — still older than the Giza pyramids or the Sumerian ziggurats.

“If these dates are verified,” says Dr Danny, “Gunung Padang may be the oldest megalithic site in the world.” This would drastically shift our timeline of civilisation — positioning Southeast Asia, not the Near East, as one of humanity’s earliest cultural heartlands.

Atlantis in Asia?

Plato’s descriptions of Atlantis — in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias — speak of a powerful civilisation on a large peninsula, rich in natural resources, elephants, and surrounded by a tropical climate. Contrary to popular belief, Plato never claimed Atlantis was in the Atlantic Ocean.

Dr Danny sees a striking parallel: “The geography matches almost exactly — the elephants, the gold and tin, the climate, even the land's shape. All of it fits Sundaland far better than anywhere else."

The philosopher also described Atlantis disappearing in “a single day and night of misfortune.” This could mirror the initial catastrophic flood phase that Dr Danny believes submerged large parts of Sundaland in a geologically short period.

Echoes in culture, language, and myth

Flood myths are ubiquitous in Southeast Asia — from tales of sunken kingdoms to vanished lands — often passed down through oral traditions. The region’s linguistic diversity is among the highest in the world, hinting at complex prehistoric societies whose records may have been lost to time and sea.

Some researchers even draw parallels between Indic epics like the Mahabharata and regional versions found in Indonesia, Malaysia, and Cambodia — suggesting possible pre-Indic cultural connections or earlier storytelling traditions rooted in Sundaland.

Why mainstream archaeology remains skeptical

Despite intriguing data, the Sundaland hypothesis remains outside conventional academic consensus. Much of this, Dr Danny suggests, stems from institutional inertia. Southeast Asian history is typically viewed through the lens of Hindu-Buddhist kingdoms that arose after 100 CE, with earlier periods poorly understood or under-researched.

Additionally, the tropical climate accelerates biological decay, making archaeological preservation challenging. Many promising sites are buried beneath jungle, volcanic ash, or sea sediment, and underwater archaeology in the region is still in its early stages.

A call for interdisciplinary research

Dr Danny believes the key lies in collaborative research across fields — from geology and archaeology to oceanography, genetics, and linguistics. He also advocates applying modern dating techniques to famous landmarks like Borobudur and Angkor Wat, which he says may be older than assumed if studied thoroughly.

Gunung Padang is just the beginning. His team is now collecting data from dozens of other megalithic and submerged sites across the Indonesian archipelago — some unknown to the public, others still awaiting excavation.

A new chapter in the human story?

“If we study these places properly,” Dr Danny says, “they could reshape not just Indonesian history — but the entire global story of civilisation.”

Whether or not Sundaland proves to be the fabled Atlantis, one thing is clear: Southeast Asia holds untapped clues to humanity’s deep past. As scientists uncover more from beneath the forest canopy and ocean floor, our understanding of where we came from — and how civilisation truly began — may be on the brink of transformation.