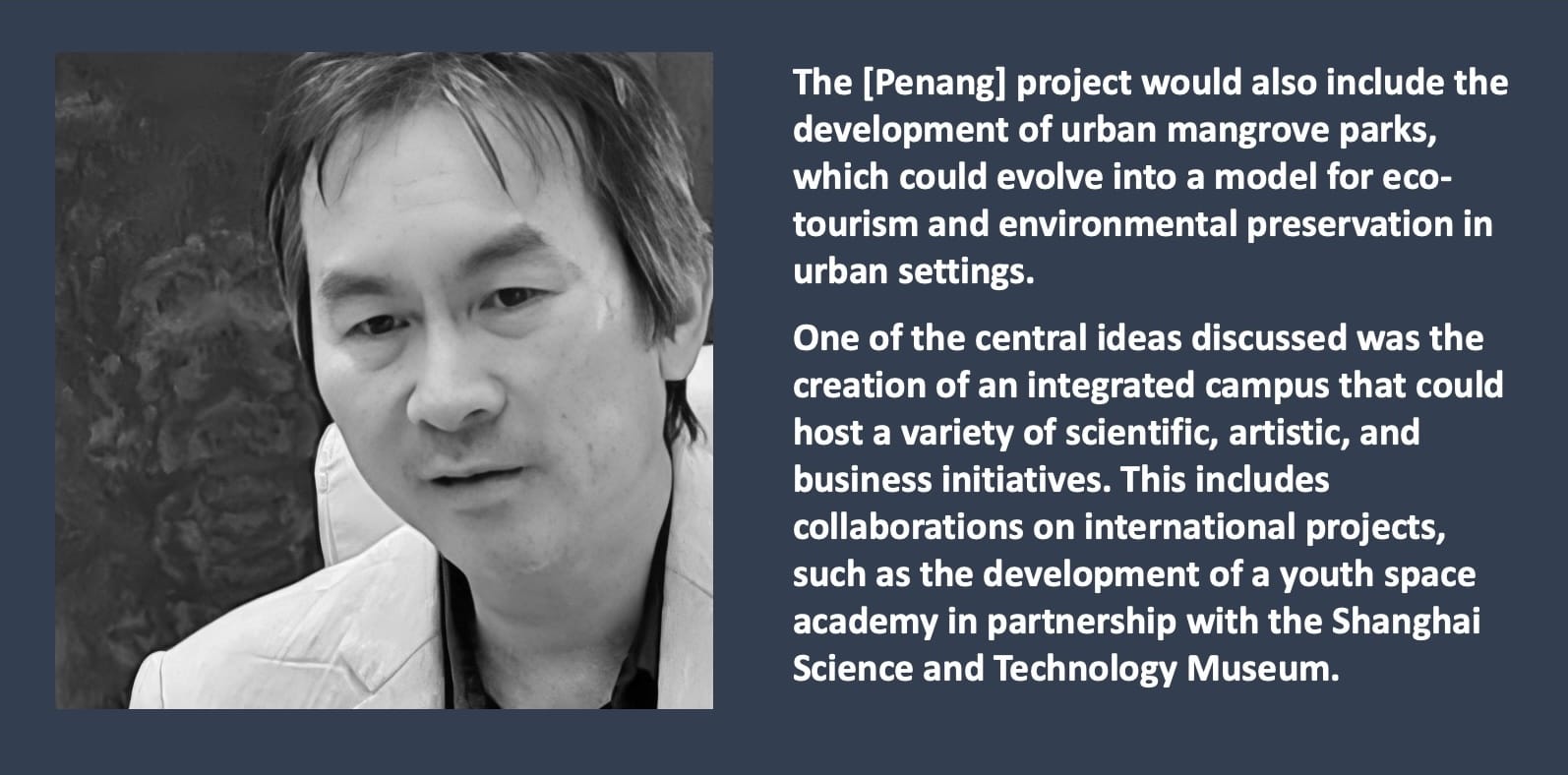

- The proposed Penang Urban Mangrove Park–Art & Enterprise Campus exemplifies a new model where education, research, business, and living spaces converge to foster sustainable, knowledge-driven development in Southeast Asia.

- Envisioned as part of a broader regional network, the campus is envisaged to connect Penang with neighbouring cities through emerging technologies like eVTOLs and AirFish8 water taxis, enabling a dynamic ecosystem of collaboration.

- Prof Tay Kheng Soon’s concept of 1km² enterprise reimagines urban environments as “learning-living laboratories” designed for synergy, resilience, and innovation at the heart of economic and industrial zones.

By Anansa Jacob

THE IDEA of the “enterprise campus” is gaining traction across Southeast Asia as universities and cities alike begin to rethink their roles in a rapidly changing world.

At a recent workshop in Penang, two key figures — veteran Singaporean architect and academic Prof Tay Kheng Soon and New Asia Currents co-founder Winfred Khoo — shared complementary visions for the transformation of higher education and urban development in the region.

Khoo, who has been spearheading several projects to position Penang as a key educational, technological and artistic hub for the region through the Commonwealth of World Chinatowns (CWC), highlighted a bold proposal centred around enterprise campuses.

Hub for knowledge

Initially conceptualised in Singapore by Prof Tay and his team as a new university model, the project has evolved into the proposed Penang Urban Mangrove Park—Art & Enterprise Campus.

This vision aims to foster a hub where people can live, work, invent, and create in a single location, drawing inspiration from innovative examples like Nanyang Technological University (NTU) in Singapore.

The goal of the enterprise campus is to merge research, business, and education, with a focus on translating intellectual discoveries into practical solutions for society.

Khoo hopes it will feature a mix of institutes and enterprises, with research areas such as mangrove desalination, integrative health, and the cutting-edge study of fourth-phase water, carbon and energy institute.

Connecting the region

The project would also include the development of urban mangrove parks, which could evolve into a model for eco-tourism and environmental preservation in urban settings.

One of the central ideas discussed was the creation of an integrated campus that could host a variety of scientific, artistic, and business initiatives. This includes collaborations on international projects, such as the proposed International Youth Space Academy in partnership with the Young Cosmonaut School, Gagarin Cosmonaut Training Centre and the Shanghai Science and Technology Museum to be co-organised with Tech Dome, the Penang State Science Centre.

The region’s ambitions extend beyond the local scale, envisioning a network of cities — Phuket, Langkawi, Medan, and Bandar Aceh — that could be linked together via electric vertical takeoff and landing (eVTOL) aircraft, such as AirFish8 water taxis.

A unique aspect of the development is the emphasis on “umami architecture”, a concept that Prof Tay is championing, which seeks to blend environmental sustainability with innovative design.

By the planned 2032 milestone, the aim is to have a fully realised urban mangrove park and enterprise campus, serving as a model for sustainable development and technological advancement in Southeast Asia.

Promoting a new kind of learning

Meanwhile, Prof Tay Kheng Soon brings a wider regional lens to the discussion, rooted in decades of architectural and urban theory.

He describes the world as being in a “very transitional phase,” where existing models of development — particularly in cities like Singapore — are increasingly constrained by rising costs, global fragmentation, and administrative silos.

Tay argues that a completely new kind of learning environment is needed to encourage experimentation and innovation. His proposal centres on the Johor-Singapore Special Economic Zone (SEZ), a massive project five times the size of Singapore. He sees it as an ideal site for pioneering large-scale enterprise campuses: live-in, self-contained communities where students each would “live, learn, and earn”.

Featuring housing start-ups, academic institutions, and support infrastructure such as schools and family housing, these campuses would be placed near financial and industrial centres — “where money and brains come together,” Tay says.

It’s a model inspired by Silicon Valley and Boston, where proximity and critical mass generated enduring innovation. Tay proposes looking into setting up the enterprise campus close to Forest City, which is itself on track to be revamped as a financial centre.

Where people can live, learn and earn

For this site, Tay reveals plans for three enterprise campuses, each with a size of 1km sq. “Each one will have about 60,000 students who will live, learn and earn there,” he says.

“[You will] have 180,000 people living and learning there, right next to where the money is. Now this is crucial; when you put money and brains together, I think this is the formula for tremendous vitality.”

However, he acknowledges the challenges of implementation. In Singapore, although his enterprise campus proposal for NTU was well-received by agencies like the Urban Redevelopment Authority (URA) and senior policymakers, administrative rigidity remains a major barrier.

In many ways, Penang could offer a middle ground — combining local governance flexibility with a rich urban ecosystem. Tay praises Penang’s existing vibrancy, and acknowledges the potential for integration rather than reinvention.

He suggests that a pilot enterprise campus could be developed in a suitable Penang coastal area, with modular housing atop cultural and research facilities. Unlike isolated innovation parks, this model thrives on embedding the campus within the an active city.

For a bold new future

Both Khoo and Tay emphasise the need for compactness and proximity — not just in physical terms, but in the way people, disciplines, and institutions interact.

In this view, enterprise campuses are not just educational upgrades; they are blueprints for a new urban typology, where the boundaries between university, workplace, and home dissolve into a dynamic ecosystem.

For Penang, and other Southeast Asian cities facing similar transitions, the enterprise campus is more than a spatial concept. It’s a response to deeper structural shifts: the need to retain talent, stimulate innovation, and build resilience in the face of global volatility.

The key lies in designing for synergy, flexibility, and shared purpose. Prof Tay envisions a future where entire cities become “learning-living laboratories” — dynamic environments where education, innovation, and everyday life are deeply intertwined.

It’s a bold reimagining of urban space, one that blurs the boundaries between campus and city, and offers a compelling blueprint for how Southeast Asia might reinvent itself through knowledge-driven development.