- London-based scholar and best-selling author Ian Hudson shares his views and researches on the Chinese explorer’s discoveries in the early 15th Century. Hudson specialises in ancient seafaring civilisations and global maritime exploration.

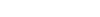

- Hudson began collaborating with historian Gavin Menzies in 2002, contributing to various projects such as book publications, 1421 and 1434; the “1421” exhibition in Singapore, and a television documentary series.

- There were compelling evidence of Zheng He’s arrival in America such as the Pizzigano map of 1424, and the Chinese DNA and artefacts.

By Sebastian Lim

FOR CENTURIES, the story of Christopher Columbus discovering America in 1492 has been ingrained in popular history. However, research by Gavin Menzies and Ian Hudson suggests that the Chinese, under Admiral Zheng He, may have reached the Americas decades before Columbus. This theory challenges conventional historical narratives and raises fascinating questions about pre-Columbian global exploration.

Voyage of Zheng He

Gavin Menzies’ book, 1421: The Year China Discovered the World, argues that a massive Chinese fleet set sail in 1421 under Emperor Zhu Di’s orders. Led by Zheng He, a trusted eunuch admiral, this fleet was the largest of its time, with ships up to 400 feet long — far larger than the vessels used by European explorers in later centuries.

The fleet’s mission was to explore, establish trade relations, and bring foreign nations into China’s tribute system. However, upon their return, they found that China had undergone a political shift. The new emperor had abandoned maritime exploration, and much of the historical record of Zheng He’s expeditions was erased. This left behind tantalising clues but no official recognition of the great voyages.

According to Menzies and Hudson, Zheng He’s fleet travelled far beyond Africa, possibly reaching the Americas in the early 1420s — more than 70 years before Columbus.

Evidence for a Chinese discovery of America

One of the most compelling pieces of evidence supporting this theory is the collection of maps including the Pizzigano map of 1424, which depicts Caribbean islands long before Columbus’ famous voyage. How could a Venetian cartographer have mapped these islands unless someone had already explored them? Other maps, such as the Fra Mauro map of 1459, contain details of places that had supposedly not been discovered by Europeans at that time.

“I find it hugely compelling that the whole world was charted with great accuracy before many of the European voyages of ‘discovery’ had taken place,” says Hudson. “How do you discover a place for which you already have a map? How could Columbus, Magellan and others be lauded as the discoverers of these far-flung lands if they had admitted to seeing them on maps in their possession? And who could have drawn those maps? Those are the questions that we are trying to answer!”

Beyond maps, there is physical and cultural evidence suggesting pre-Columbian contact between China and the Americas. One of them is the Chinese DNA in Native American populations.

Genetic studies have shown significant “recent” East Asian ancestry in some indigenous groups in the Americas, suggesting migration or contact via the Pacific rather than only the Bering land bridge.

Next are the Chinese artefacts found in the Americas, such as the Ming-era ceramics and metal objects that have been discovered in locations such as California and Peru. One particularly intriguing find is the Baby Buddha artifact in Australia, which some researchers believe was left behind by a shipwrecked Chinese expedition.

There is also the botanical evidence where crops like Asiatic rice, coconuts, and sugarcane were found in the Americas before European colonisation, suggesting early transoceanic exchange.

Shipwrecks, for Hudson, are another smoking gun — the “Holy Grail for 1421”! He adds: “If we can locate a Chinese shipwreck in the New World and date it to pre-Columbian times then we have proved the theory. The problem to date has been cost — salvage of wrecks is prohibitively expensive, so we must wait until either funds are raised, or we find a wreck that isn’t buried deep under vast masses of sand, silt or water! There are plenty of them out there!”

Meanwhile, accounts from early Spanish explorers from conquistadors such as Francisco Vázquez de Coronado describe encounters with indigenous people who bore striking similarities to Asian cultures. Some even recorded sightings of large ships on the west coast of North America, possibly belonging to Chinese merchants.

According to Hudson, “You are clearly able to read, to this day, accounts of the conquistadores who arrived in the Americas to find proof that Chinese explorers had been there before them.

“They described seeing wrecks of Chinese junks on the shores, and were taught by the native peoples that visitors from China had crossed the Pacific and traded with them in the past.”

Hudson’s role in Menzies’ research

Ian Hudson played a crucial role in developing the 1421 theory. After earning a degree in Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin American studies from the University of Bristol, he joined Menzies’ research team. His linguistic skills were invaluable in analysing those early Spanish and Portuguese texts, which contained references to pre-Columbian exploration.

Hudson contributed to multiple projects, including setting up the 1421 team of researchers, and the website www.gavinmenzies.net where researchers and history enthusiasts could share findings and discuss evidence. He also helped organise exhibitions, talks, and documentary collaborations to expand the reach of the 1421 hypothesis. He then set up the 1421 Foundation, a US-based non-profit research entity, with a view to testing and developing the hypothesis with scientific rigour.

As new information emerged, Menzies and Hudson published further books, including Who Discovered America?, which explored the idea that global exploration occurred thousands of years before Zheng He’s expedition. They questioned the widely accepted Bering Strait migration theory, arguing that ancient mariners had likely used ocean currents for long-distance travel.

“Our most recent book was written in the light of research which recognises that man has been using Mother Nature’s abundant provision of wind and water for much longer than we have given him credit for, using the world's oceans as transport corridors for thousands of years,” Hudson adds. “The currents in the North Pacific flow in a great loop carrying boats north from China, past Japan then swinging east past the Aleutian and Kurile islands to Alaska, and then south along the American coast to Central America.

“The more we think about the Beringia theory of populating the Americas, the more ridiculous it becomes. Our conclusion was that only armchair academics could believe in the Bering Straits theory of migration. It is another story to boost the myth that trans-oceanic journeys were impossible before Columbus.”

Rewriting history

If Zheng He’s fleet did reach the Americas, why is this not common knowledge? The answer lies partly in Eurocentric historical narratives. For centuries, Western historians have emphasised European achievements while overlooking non-European contributions to exploration and cartography. Additionally, China’s decision to withdraw from international affairs in the mid-15th century meant that much of its maritime history was lost or deliberately erased.

The 1421 hypothesis remains controversial, with some scholars questioning its claims due to the lack of concrete archaeological proof. However, discoveries such as ancient shipwrecks in the Americas and DNA evidence continue to fuel interest in the topic.

Gavin Menzies and Ian Hudson’s work has encouraged a re-evaluation of how history is written. It reminds us that history is not static but an ever-evolving field where new evidence can challenge long-held beliefs. Whether or not Zheng He’s fleet truly reached America, the idea that ancient civilisations were more interconnected than previously thought is a fascinating possibility.

In the end, the story of human exploration is far more complex than simple narratives of European discovery. If nothing else, the 1421 theory serves as an invitation to look beyond traditional history books and consider a world where the Chinese, and perhaps many other civilisations, explored the world long before Columbus.