- Forging a Nanyang visual language: Yong Mun Sen transformed tropical landscapes and everyday life into a distinctive Nanyang aesthetic, blending expressive abstraction with direct observation through watercolour.

- Art within diaspora and historical change: Yong's practice reflected the Chinese diaspora’s social consciousness, responding to migration, colonialism, war, and cultural survival in Malaya and Singapore.

- Institution-building and artistic legacy: Through art societies, education, and advocacy, Yong helped shape the foundations of Nanyang art, influencing generations and key institutions such as Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts.

By Yiming Yin

GOLDEN sand and emerald seas, coconut shadows swaying, plantation labourers toiling back and forth—these are the everyday scenes of Nanyang. It was also in this natural environment that Yong Mun Sen began his self-taught artistic journey. Amidst the equatorial humidity and the cross-cultural currents of port cities, he forged watercolour into his central artistic language.

Blending expressive abstraction with realist observation, Yong distilled a visually unmistakable “Nanyang” aesthetic. His brushwork was economical yet richly layered, capturing both the luminous interplay of land, sea and tropical flora, and the rhythmic pulse of daily life in rubber plantations, fishing harbours, temples, and bustling streets. This essay tries to employ a dual narrative approach to examine the reciprocal influence between Yong Mun Sen’s artistic journey and the geopolitical landscape he inhabited.

Chinese diaspora and Nanyang’s historical flux

The term “Nanyang” (南洋), traceable to Song Dynasty texts, originally denoted the southern seas beyond China’s Jiangnan coast, off the south bank of the Yangtze River. Over time, it evolved to signify not only Southeast Asia’s coastal landscapes but also the cultural tapestry woven by the oceanic strait area’s history. Yong Mun Sen’s life and artistic practice witnessed and mirrored this land’s transformations.

Born in 1896 to a plantation family in Sarawak, Yong's ancestors migrated during the late Ming Dynasty following Zheng He’s maritime expeditions. His birth coincided with the second wave of Chinese migration post-Opium Wars, which amplified Chinese cultural influence in Malaya.

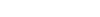

Kek Lok Si Temple (極樂寺), the largest Chinese Buddhist temple in Southeast Asia, was also built during the 19th and 20th centuries’ turn, and was treated as both a spiritual bridge linking mainland China and the diasporic Nanyang – later it also became a vital motif in Yong’s work (Figure 2).

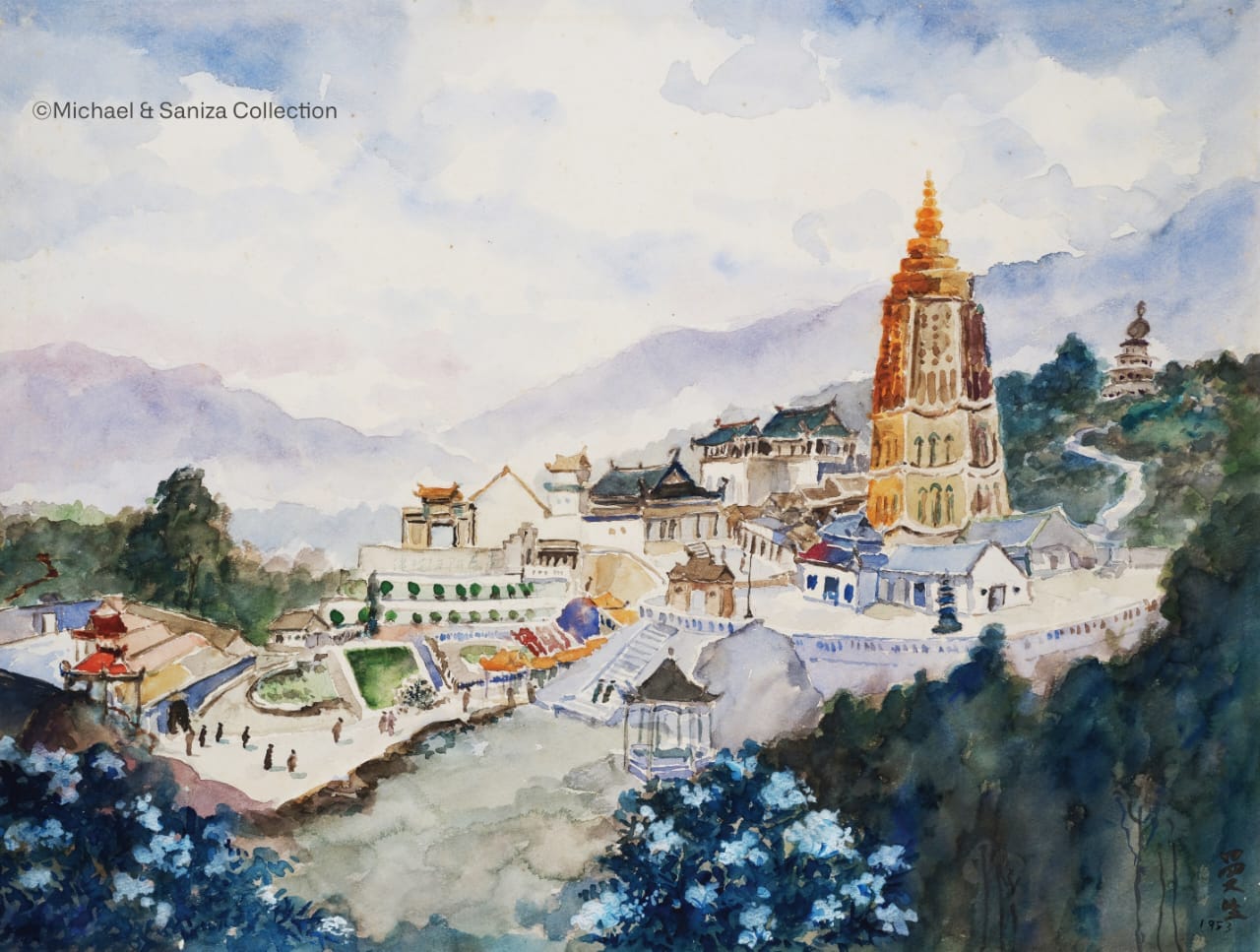

Modern Malayan history was profoundly shaped by the British East India Company’s Straits Settlements (established 1826), which dominated the peninsula until its 1946 restructuring into the Malayan Union. European influences lingered as Penang and Singapore emerged as global trading hubs (Figures 3–4). These ports became crucibles of cross-cultural exchange: Sumatran Muslims embarked on pilgrimages via Penang; Sun Yat-sen founded branches of Tongmenghui (同盟會, Alliance for Democracy) in Penang and Singapore, which laid solid foundation for the 1911 Revolution that called an end to China's last imperial dynasty. Such dynamism epitomised Nanyang’s role as a cultural nexus.

The rise of local art associations

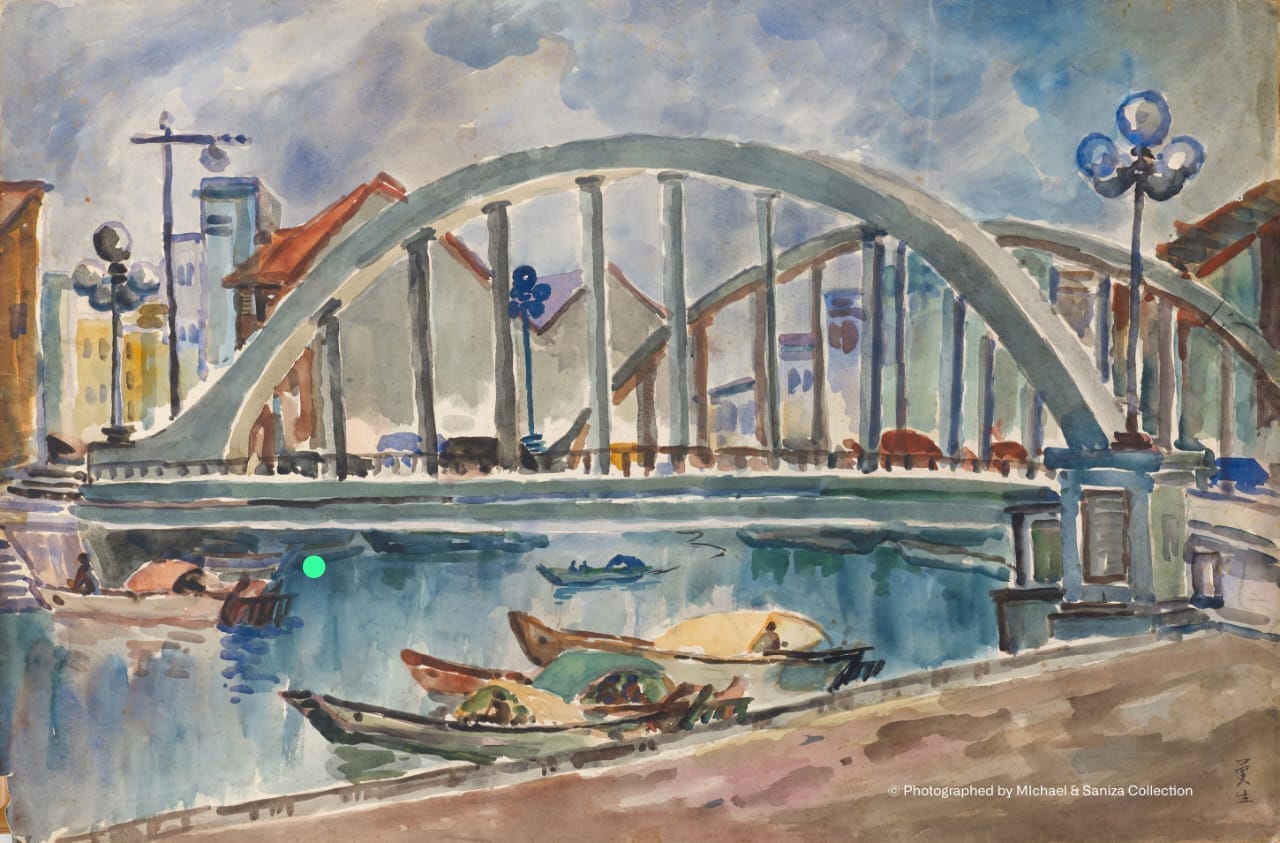

This cultural dynamism profoundly shaped the artistic sphere. By the mid-1930s, Penang and Singapore witnessed a burgeoning Chinese-artist-centred cultural milieu, where art enthusiasts spontaneously formed diverse grassroots associations. Naturally, this included Yong Mun Sen at his creative peak, who co-founded several collectives: Penang Chinese Art Club (檳城華人美術研究會, est. 1936), where he served as vice-chairman, Singapore Society of Chinese Artists (新加坡華人藝術協會, est. 1936) (Figure 5), Western-style groups like the Penang Impressionist Group (est. circa. 1935). Among these, the Ying Ying Art Society (嚶嚶藝術展覽會, inaugurated 1936)—whose name’s pronunciation imitates the sound of an infant’s cry—sought to “ignite our community’s artistic awareness (集合藝術創作,公開展覽)” by “gathering creative works for public exhibition (以引起吾僑人士對藝術之注意).” Yong contributed 20 oil paintings, 15 watercolours, 12 photographs, and 3 sculptures to the first edition of Ying Ying’s public showcase, establishing himself as the most exhibited artist that year.

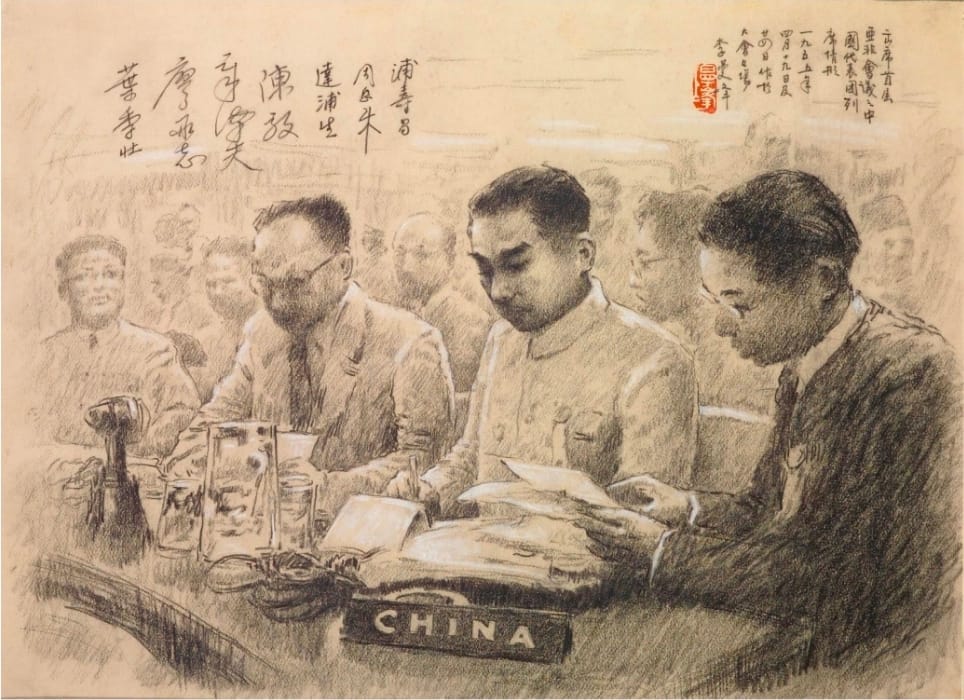

Beyond reflecting social realities with their paint brushes, what is especially commendable was how these Chinese artists cared about Chinese societal development scenes and were actively engaged in the Chinese national affairs. In February 1931 (the 20th year of the Republic of China), Yong Mun Sen, together with Tan Seng On, Chong Pai Mu, Ye Yingjing, Ooi Hwa, Chen Lan, as well as others from across Penang, Ipoh, Kuala Lumpur, and Singapore, initiated a self-financed charitable art exhibition as a means to gather relief fund for the severe famine in Shandong. (Figure 6)

Art education and legacy inheritance

While reaching out to the public and promoting art in the form of public exhibitions, Chinese artists represented by Yong Mun Sen championed art education as vital for cultural continuity. Firstly, arts education is about passing on techniques and spirit inheritance. For example, Lee Cheng Yong (李清庸, 1913-1974), who carried Yong’s watercolor characteristics and co-founded the Penang Chinese Art Club with Yong Mun Sen in 1935, was one of the students from the Wei Kuan Painting Studio (蔚觀畫室), Yong’s studio in the 1920s. In addition, arts education is about establishing connections.

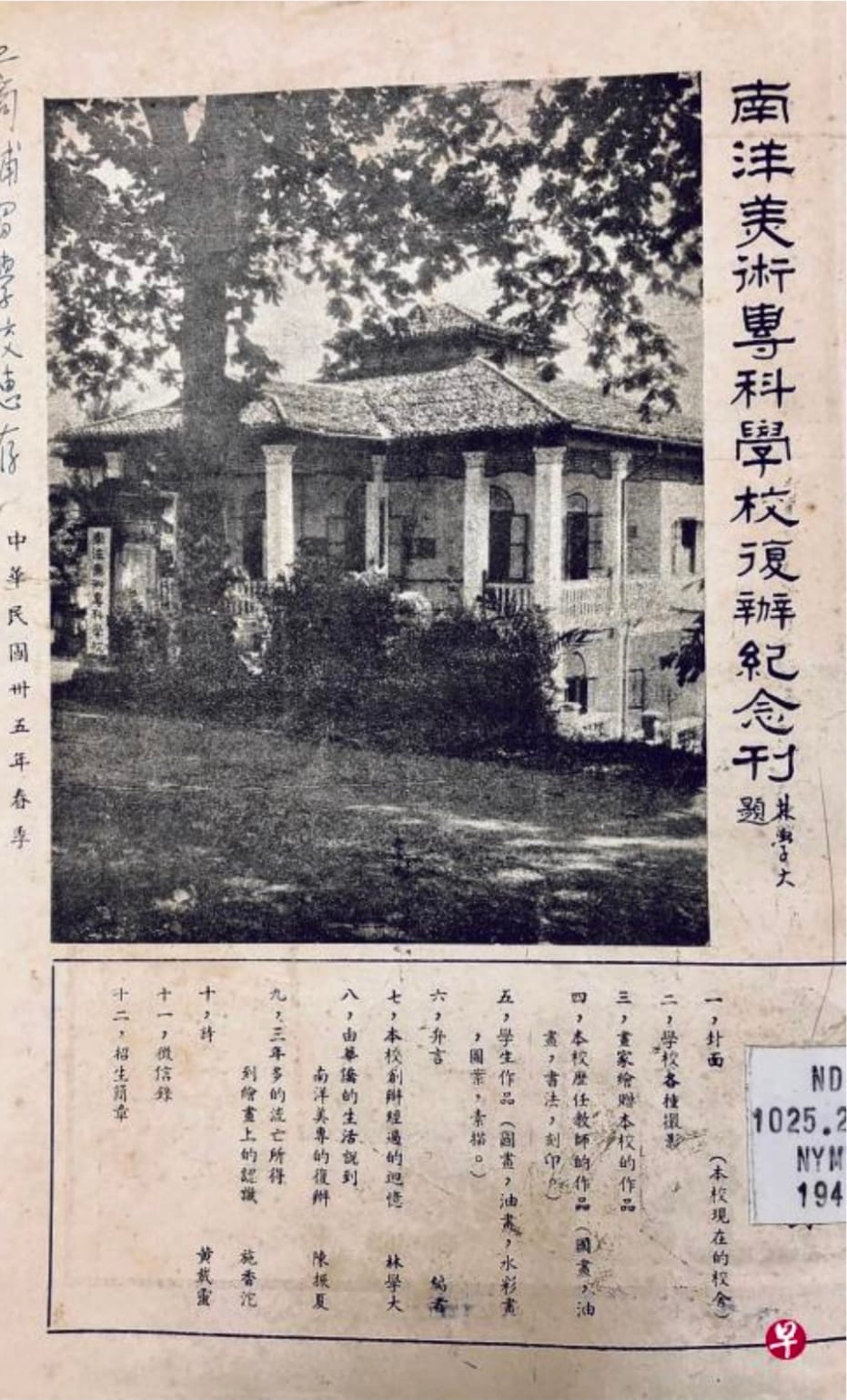

Despite being separated by 700 kilometres of physical distance, Penang and Singapore maintained a strong relationship between the artists of the two places, often co-organising events, and the Chinese Art clubs of the twin cities were founded in the same year and under the leadership of almost the same group of people. The most pivotal historical node of art education in Malaysia and Singapore came in 1938. Spearheaded by Yong Mun Sen's advocacy and Xu Beihong (徐悲鴻)’s philosophy of "infusing Western techniques to enrich Chinese traditions (以西潤中)," Lim Hak Tai (林學大, 1893-1963), who had taught at Xiamen Academy of Fine Arts and Jimei Normal College, gathered a group of graduates from Shanghai, Beiping, Xiamen, and Paris art schools to found the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts (NAFA) in Singapore, where a groundbreaking concept of “Nanyang style” was later proposed and pioneered.

Yet history seldom flows smoothly. Just as these educational roots began to spread, World War II (1941–1945) erupted. Japanese military aggression severely crippled local economies, livelihoods, and cultural development. Under the Japanese cultural oppression, the Chinese art society’s activities were surveilled, and much photographic evidence of the groups were burnt as a precaution.

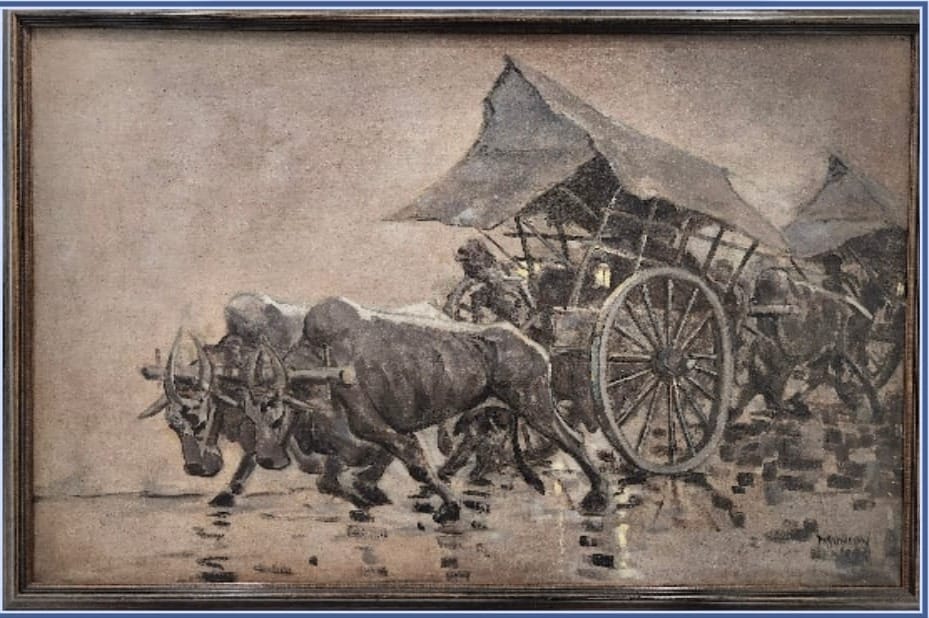

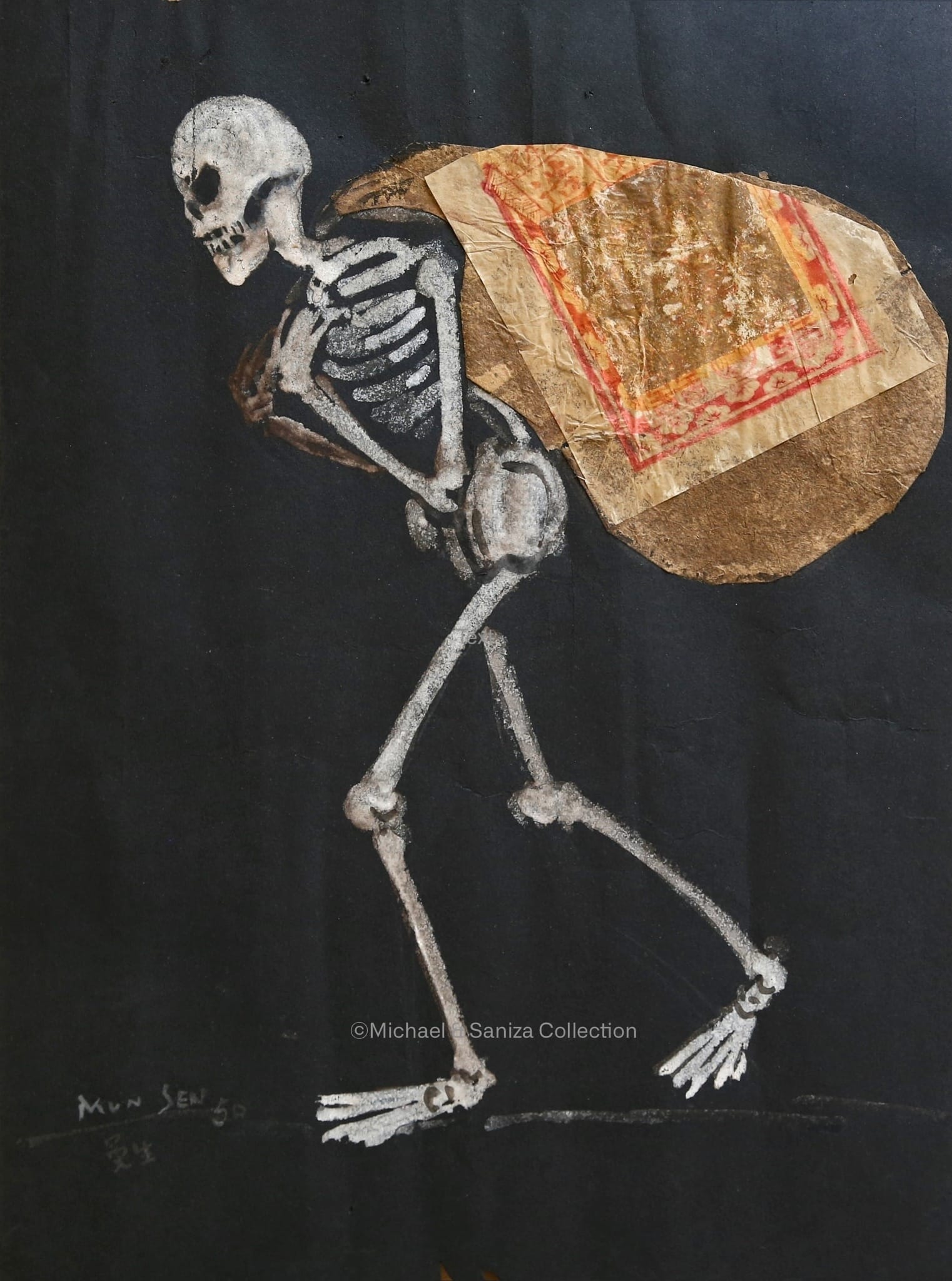

Yong Mun Sen’s work End of the Day (Figure 7) captured this era’s anguish through a dim, desaturated palette and heavy, oppressive themes, rendering with visceral clarity the burdens borne by civilians. This painting stands as a haunting time capsule of wartime existence.

Under the onslaught of Japan’s southward advance, the newly established NAFA—fresh from graduating its inaugural class—suspended operations in 1942. Yet “though flames may scorch the earth, roots survive beneath the ashes” (野火燒不盡,春風吹又生), within a month of Japan’s surrender in September 1945, Principal Lim reignited NAFA’s mission and resumed the teaching (Figure 8). This unwavering commitment to education became institutional DNA and has been passed down from generation to generation, cementing NAFA as the cradle of “Nanyang Feng.

In 1953, as the turbulent 1940s receded, the Penang Art Society emerged under Loh Ching Chuan (1907-1966)’s leadership. It united members of Yong Mun Sen’s Penang Photography Society with diverse artistic talents. This association embodied Yong’s early vision—a seed of “artistic dissemination” planted during the Ying Ying exhibitions, now flourishing after wartime trials. Members launched annual art festivals, exchange exhibitions, lectures, and calligraphy competitions, even sponsoring overseas study tours—a legacy thriving to this day.

Against the larger global backdrop, the Bandung Conference was held in Indonesia in 1955 (Figure 9), which was the first international conference held by Asian and African countries without the participation of Western colonial powers. The gathering by all means ignited the “dawn of decolonisation.”

In 1963, a year after Yong’s passing, the federal constitutional monarchy, Malaysia, that brought together the former Federation of Malaya, North Kalimantan, Sarawak, and Singapore, was proclaimed. Following that, Singapore gained independence in 1965, officially announcing the beginning of a new chapter of “post-colonial” life in the South Seas.

Regional stability catalysed cultural revival. Scholars began reexamining history through modernist and postcolonial lenses, while art historians spotlighted Chinese artists deeply rooted in Malayan soil—those who fused Eastern and Western techniques with local sensibilities.

In 1979, National Art Gallery of Malaysia in Kuala Lumpur formally enshrined the terms “Nanyang Style/Fengge” and “Nanyang School” in its landmark retrospective exhibition Pameran Retrospektif Pelukis-Pelukis Nanyang, leading the gradual filling of the gap in Western-dominated art history documentation. Detailed research on Yong Mun Sen's interaction with the Nanyang region has been examined by recent scholars and was meticulously published by Asia Society (Hong Kong) in 2023, which will not be repeated in this article.

Epilogue

Ancestral roots in Guangdong, birth in Sarawak, education in Tai Po in Guangdong, China, and migration back to Penang and Singapore subsequently—these multifaceted experiences defy any singular national identity in defining Yong Mun Sen. "Nanyang," with its profound historical resonance, perhaps best encapsulates the essence of both the artist and his oeuvre.

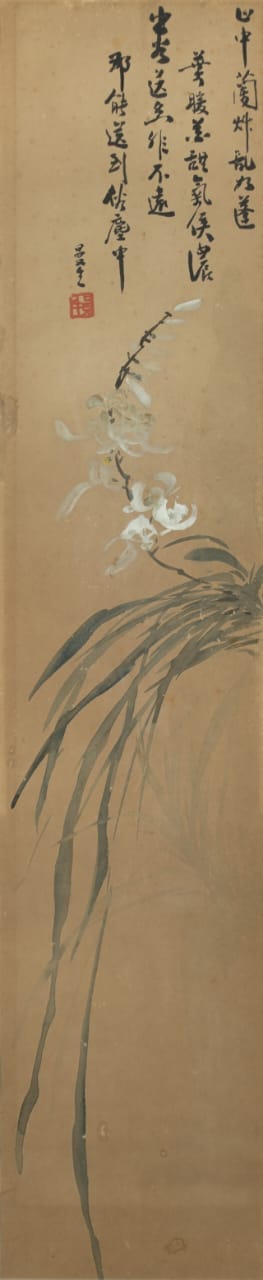

Today, the influence of this "Father of Malaysian Art" remains pervasive. Like the tangled rainforest vines in his paintings, his artistic legacy has permeated the very fabric of Nanyang culture: from the scholar-literati heritage revealed in early ink works like Orchid (Figure 10), to the fieldwork documenting Nanyang villages through scenes like the luxuriant forest the villagers lived in, as well as the fishing nets and kelong they use on a daily basis (Figures 11–13) during his prime, and to the existential inquiries in late-career pieces such as Death Pursuit of Wealth (Figure 14), his palette remained perpetually steeped in the salt of Nanyang, offering invaluable clues for understanding this region’s cultural landscape.

Yong Mun Sen’s creative career mirrors Nanyang art’s evolution: from colonial confines toward globalisation and cultural self-awareness. The gilded roofs of Kek Lok Si and laterite soils of plantations in his works carry not only the spiritual legacy of Chinese migrants but also forge the aesthetic foundations of the “Nanyang feng”—watercolours diffused in humid air, brushstrokes nourished by civilisational encounters—transcending borders as cultural birthmarks.

As sunlight still dances on Marina Bay’s waters today, seeds sown by Yong and his contemporaries have branched through Nanyang Academy’s lineage into forests. Their canvases—vessels bearing rubber plantation mists, fishing-port sunsets, gunpowder, and reconstruction’s dawn—sail toward identity’s deep harbour. What endures is not merely art, but the soul of equatorial lands, forever seeking its own form.

- This article is inspired by the Curator Masterclass talk given by Kwok Kian Chow on April 11, 2025, in Hong Kong. It is reproduced in NAC in conjunction with the 130th Anniversary of Yong Mun Sen's birthday on Jan 10, 2026. Story and photos courtesy of Michael Yong-Haron and Saniza Othman.