- Revisiting the global map using cartographic evidence of early Chinese knowledge of the Americas

- Archaeological and architectural traces of Chinese presence in North America

- Dr Sheng-Wei Wang emphasises the importance of a cross-disciplinary, global re-evaluation of maritime history

By Sebastian Lim

MORE THAN 600 years ago, Admiral Zheng He commanded the mighty Ming treasure fleets across the Indian Ocean. But could those ships have reached the shores of the Americas — decades before Columbus? Dr Sheng-Wei Wang, a Hong Kong-based physicist, historian, and founder of the China–US Friendship Exchange, believes so.

In this Part 1 of the exclusive interview, she shares compelling cartographic, and archaeological evidence that suggests the Chinese reached the New World long before Europeans did. This theory challenges long-standing Eurocentric narratives of exploration history which may require a re-examination of early maritime exchanges.

Curious map that sparked a global inquiry

Dr Wang’s journey began with Gavin Menzies’ controversial 2002 book, 1421: The Year China Discovered America. “Though speculative,” she recalls, “it forced me to ask: what if there’s some truth to it?”

Her real breakthrough came in 2010 while hosting a visiting researcher in Hong Kong. He brought with him centuries-old European maps that seemed to show the Americas — labelled with names traceable to Ming China. “That moment awakened the scientist in me,” she says. “I needed to investigate for myself, systematically.”

By 2013, she had embarked on a full-scale investigation: “Did Zheng He really stop at East Africa — or did he go further?”

Global sources, local clues

Dr Wang’s research draws from a diverse trove of primary sources — both Western and Chinese. These include: Gavin Menzies’ 1421 series; Paul Chiasson’s studies of Chinese architecture in Nova Scotia; Siu-Leung Lee’s map analysis of the Kunyu Wanguo Quantu map or Complete Geographical Map of All the Kingdoms of the World, 1602 (abbreviated as KWQ) by Matteo Ricci; 16th-century Chinese texts such as An Account of the Western Voyages of the San Bao Eunuch by Luo Maodeng; and survey work by British geographer TC Bell, especially in Cape Breton Island (Canada), and New Zealand.

Dr Wang has also authored several books consolidating her findings, such as The Last Journey of the San Bao Eunuch, Admiral Zheng He (2019), and most notably Chinese Global Exploration in the Pre-Columbian Era: Evidence from an Ancient World Map (2023).

The cartographic key

The most compelling evidence, Dr Wang says, lies in maps — especially Ricci’s Kunyu Wanguo Quantu or Complete Geographical Map of All the Kingdoms of the World (KWQ), printed in 1602. It contains over 1,000 place names from around the world, which Dr Wang painstakingly analysed, including 242 of these in the Americas section and found something astonishing:

Firstly, she noticed that the coordinates are Chinese, not European and they could only derive from the Chinese source because of Chinese explorations.

Next, the naming of regions is accurate to the period of discovery, around 1420s – 1428 — not the map’s printing, 1602.

“The political condition for the Americas matches a period around 1420s –1428,” she explains, “which is squarely within the active years of Zheng He’s voyages.”

“The KWQ map opened the door for many of us to ask: What if the Chinese really knew about the Americas earlier than we thought?” Dr. Wang says. “The scale, the locations, and the presence of landmasses resembling the Americas suggest that Zheng He’s fleet could have reached across the Atlantic.”

Zheng He’s massive fleet: A technological marvel

At the core of this theory is Zheng He himself, a Muslim eunuch admiral born in 1371 in Yunnan, China. Under the patronage of Emperor Yongle of the Ming Dynasty, Zheng He commanded seven massive expeditions between 1405 and 1433, sailing across Southeast Asia, the Indian Ocean, East Africa, and the Arabian Peninsula. His fleets reportedly included hundreds of ships and tens of thousands of crew members.

Dr Wang says that the capabilities of these fleets — larger, better organised, and more advanced than any in the world at the time — make it entirely plausible that they could have ventured beyond Africa and into the Atlantic. The so-called “treasure ships” measured up to 120 meters long and were equipped with sophisticated navigation tools, including star maps and magnetic compasses.

“Zheng He’s fleet was not just military — it was scientific and diplomatic,” she notes. “These expeditions were meant to project Chinese influence and establish diplomatic ties.”

Artifacts and clues in the Americas

Another strand of Dr Wang’s research focuses on physical evidence allegedly found in the Americas that points to Chinese presence. She cites discoveries by TC Bell, who surveyed the entire Cape Breton Island in 2005.

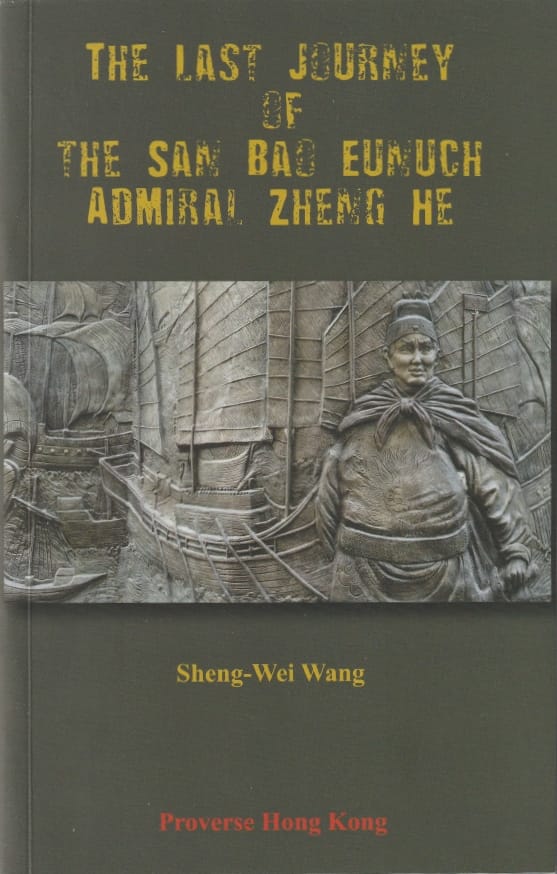

Bell discovered many remains with Chinese characteristics: extremely large, well-engineered, and well-defended settlements characteristic of a religious centre (this is the main site first discovered by the Canadian architect Paul Chiasson in 2002); an ore exploitation site, smelter ramps, and ore crushers; a group of inhumations in Chinese burial styles; roads cut out of solid rocks and part of a stone defensive gateway; canals; stonework alongside the site of a gateway; cut and carved stonework of a wall from a demolished gatehouse and remains of stone gatehouses; shore-side harbours dimensioned for Chinese treasure ships; quarried rocks; a walled barrack block compound for the Chinese mariners.

The most stunning hard evidence is at St Peter’s on Cape Breton Island where Bell found a stone (among many other stones) having holes drilled on its surface, as in Chinese splitting of rocks: a “blastless demolition agent” (a unique Chinese invention in world history) was poured into these holes followed by water to start chemical reactions which generated heat to expand and split the stone, and leave the drilled holes in black colour.

The stone was used to build the ancient canal which connected the Bras d’Or Lake and the Atlantic Ocean, and this canal separated Cape Breton Island into two islands. The KWQ is the only ancient map in the world before the 17th century to show that Cape Breton Island had become two separated islands.

“These may seem like scattered clues, but when you connect the dots, a picture starts to emerge,” Dr Wang says. “We’re seeing trade goods, possible inscriptions, even architectural similarities in some pre-Columbian structures.”

Dr Wang believes that these traces, taken together, warrant serious academic investigation. She adds that cross-disciplinary approaches — combining history, linguistics, oceanography, and anthropology — are essential to forming a holistic view of early global contact.

Challenging the Eurocentric narrative

Dr Wang acknowledges that her work has been met with skepticism in some academic circles. “The proponents of the theory that Zheng He reached the Americas must therefore work harder to provide, not just narratives, but rigorous and scientific arguments and evidence to demand recognition,” she says.

Nonetheless, interest in Zheng He’s voyages continues to grow, particularly in Asia and among independent researchers worldwide. Dr Wang is calling for a coordinated international effort to re-examine historical maps, re-date archaeological finds, and investigate cultural anomalies that may reveal a more interconnected ancient world than previously thought.

“Our world history is incomplete,” she says. “We owe it to humanity to dig deeper, literally and metaphorically.”

Read Part 2 here: Exploring Chinese influence across the Americas before Columbus

** SALUTING THE LEGEND. Click here to read our editorial and links to the main stories of our NAC Focus on Zheng He. NAC Focus, with New Asia Currents and Postscript NAC, make up the media platform of the Commonwealth of World Chinatowns (CWC)